How to improve Challenge-based learning?

Which factors determine success of challenge-based learning programs? How should the challenges be defined? How can business partners be successfully involved?

In an online workshop, staff of the academic partners in the Scaleup for Sustainability (S4S)-project exchanged experiences and analyzed the efficacy of different approaches.

Challenge-based learning (CBL) enhances innovative thinking abilities, improves team interactions, and engages students.

Especially of Volatile Uncertain Ambiguous and Complex (VUCA)- problems, this concept is useful. In cross-disciplinary teams, students learn to develop solutions to real problems of companies. Key items of CBL are the definition of a challenge (open yet concrete), the organization of a CBL (e.g. doable timeframe), the experience level and commitment of students, transparency of expectations towards participants, and tools necessary to guide the teams.

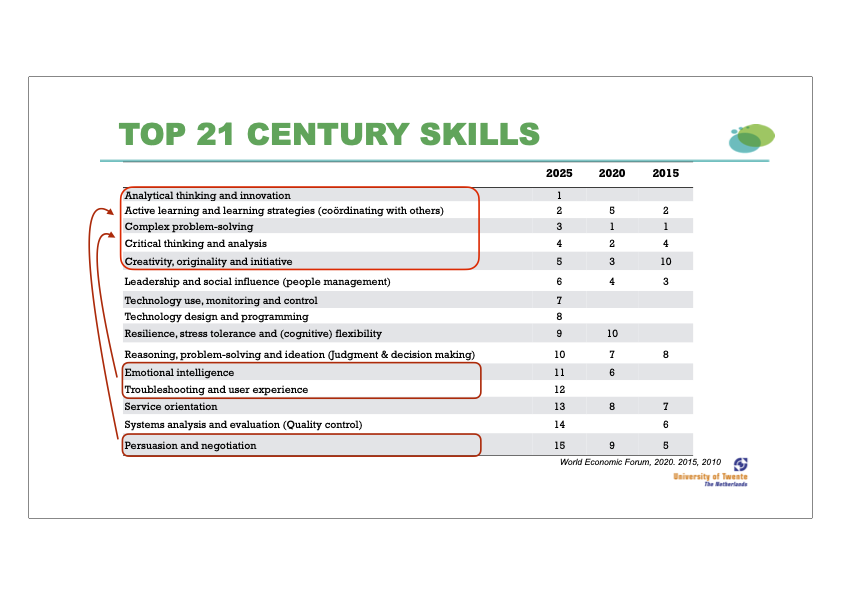

The importance of 4 themes are mentioned frequently in the evaluations: (1) time spending, time management; (2) breath/width of the programs; (3) tools, coaching, guidance; (4) organization and team processes. In CBL-programs, 21-st century skills are developed: analytical thinking & innovation; active learning / coordinating with others; critical thinking & analysis; and creativity, originality and initiative. In order to be successful in CBL-programs, emotional intelligence, troubleshooting and user experience, persuasion / negotiation are underlying skills.

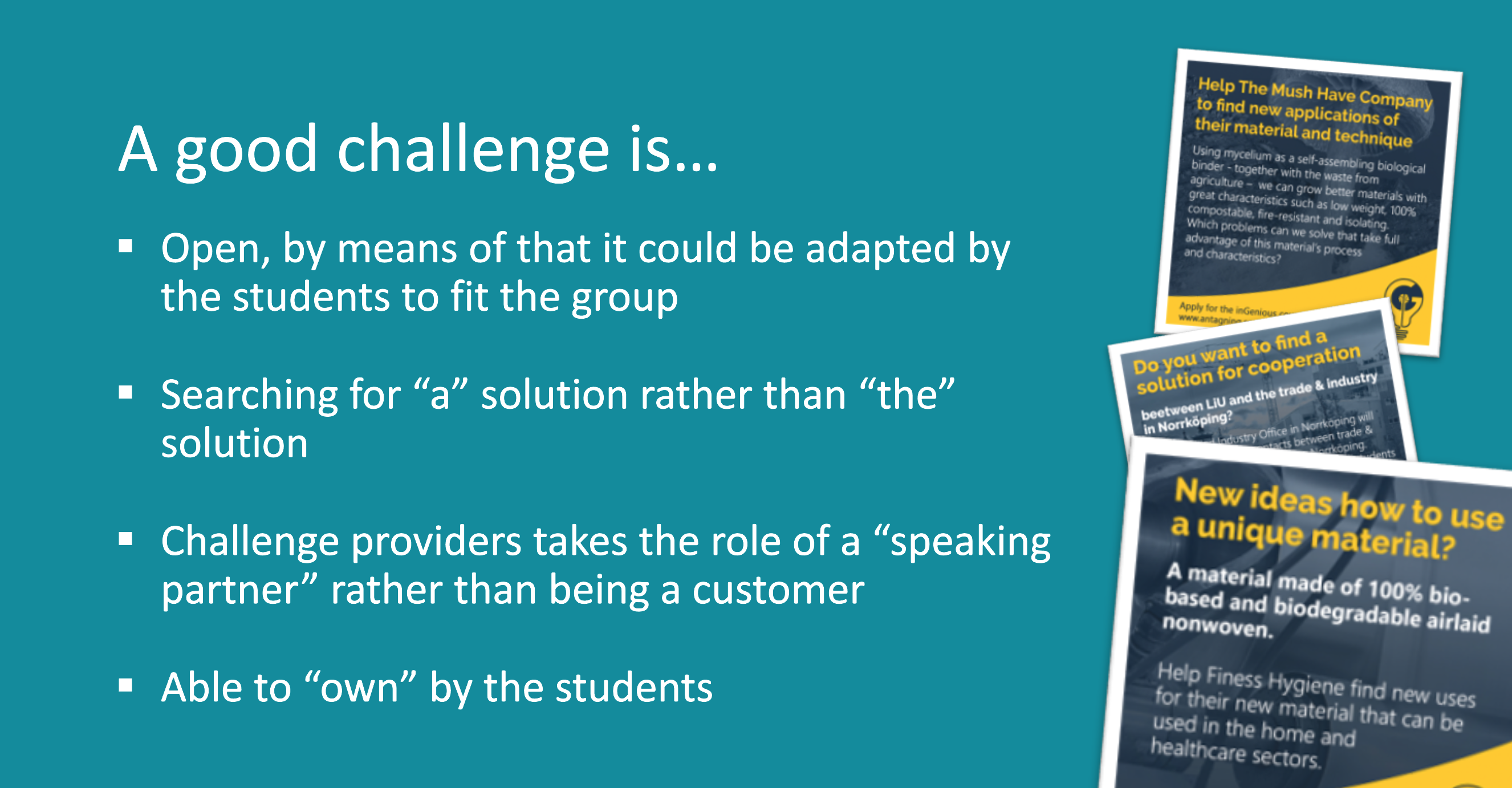

It’s important to manage expectations towards students and businesses. With transparency, students can select which challenge they are most appealing to them. A definition of a challenge should be communicated clearly with students and businesses: a challenge should be formulated not to narrowly due to the fact that this complicates ‘out-of-the-box’ thinking. Another success factor of CBLworkshops is a ‘fit’ between students and the challenges.

It’s important to be realistic and communicate how much time is available for the challenge. Team diversity (different faculties/universities/personalities/nationalities) makes CBL-programs more attractive to some students. Multidisciplinary teams enrich the creativity in teams, but are more difficult to configure. Motivation of participants is a key success factor: CBL-programs get positive ratings from students who are interested in entrepreneurship and innovation. Students who are less motivated should be given alternatives to CBL-programs because these students interfere in c.q. block healthy team dynamics. Problem-based learning varies from challenge-based learning. Defining a challenge can be considered as part of a CBL-program. We discussed useful tools for CBL-programs, e.g. the MOM-test with do’s and don’ts of receiving customer feedback: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hla1jzhan78

Before starting a CBL-program, team building is recommended.

The role of teachers and businesses in CBL-program differs: rather than instructors, teachers become coaches and businesses take the role of sparring partners. Some CBL-programs are curricular, others are extra-curricular. The later should not be too time consuming. Commonly, business partners add relevance to the learning process and illustrates theory.

Commitment, patience and transparency are crucial; an “open mind” as well. During an CBL, expectations should be adjusted and commitment ensured– both from students and from business partners. A CBL-challenge should be ‘doable’. Business partners give inputs on technical or company / industry related issues. Business partners have various roles: technological experts, data providers, and discussion partners. It is important to have an excellent relationship with the business partner. Long term partners tend to better understand what is needed on the educational side (and v.v.). Long term partners are prepared and committed. The set-up of the challenge is dependent upon the information need of the business partner.

Due to Covid19-crisis online meetings with students were organized. Digitalization provide great opportunities to increase the scale of CBL-program. A “step-by step” upscaling is recommended while learning from experience. Extra-curricular challenges most likely need some additional project funding. Curricula challenges can be funded via ordinary university budgets. Expanding to transnational or transdisciplinary CBL-programs is difficult but possible when building internal capacity at the different universities. Doing so, a CBL-program becomes more robust and is not fully dependent on individuals or external funding.

Increasingly, broad challenges, like EU “Missions” or SDG-related goals are used as a starting point for CBL-programs.

In the S4S-program, we executed shared events in which S4S-partners participated in each other’s programs. We shared experiences between universities and between universities and businesses. Not all CBL-programs need to be upscaled; sometimes business cases are more suitable for small-scale implementation.